These days, my primary motivation for engaging in projects is either irritation or spite. It’s fair to say that being critical is central to my scholarly identity. Most of my time is spent telling people how and why their scientific beliefs, assumptions, and practices are wrong1. I have always been forthcoming that my strengths do not lie in empirical matters—designing and implementing studies and the like. Being critical is really all I’ve got.

I have written about criticism previously, focusing on the question of when in one’s career it is appropriate to engage in criticism of other people’s research (tl;dr, the answer is right now). This post covers similar territory, but is more about the behavior of science as a system vs. individual researcher behaviors.

In the early days of the replication crisis in psychology, some people expressed concern that “airing our dirty laundry” could have negative consequences. Talking about failed replications, questionable research practices, p-hacking, fraud, and so on could dampen support for science in general, and psychology in particular. Some argued that the messages from scientific reform efforts could be “weaponized” by right-wing politicians looking for pretext to restrict funding for social science research. Over the years, I have heard similar concerns from psychology professors regarding teaching about the replication crisis, worried that doing so would turn students away from psychology. Notably, at least one study suggests the opposite, failing to find evidence that teaching about the replication crisis decreased students’ interest in psychology, and that it actually makes students more likely to view psychology as a scientific discipline. But people with such strong convictions are rarely swayed by contradictory data.

The worries about weaponization of scientific reform efforts have surfaced again amidst the U.S. governments’ actions to terminate research funding, terminate programs, terminate student visas, realign funding priorities, and generally assert control over scientific work. Rarely does a day go by without some reference to this problem on AcademicSky, expressed by those who are both supportive and critical of reform efforts. I have also received related questions from multiple people during my last couple of visits to other universities. As noted, all I really do these days is talk about everything that we do wrong. People ask me, with good and sincere intentions, whether I worry about being so vocal about the problems of science in the current climate. I always give the same answer: absolutely not.

That does not mean I don’t worry about the current and future climate of science. I do, very much. But I won’t stop being critical of scientific practice for two primary reasons.

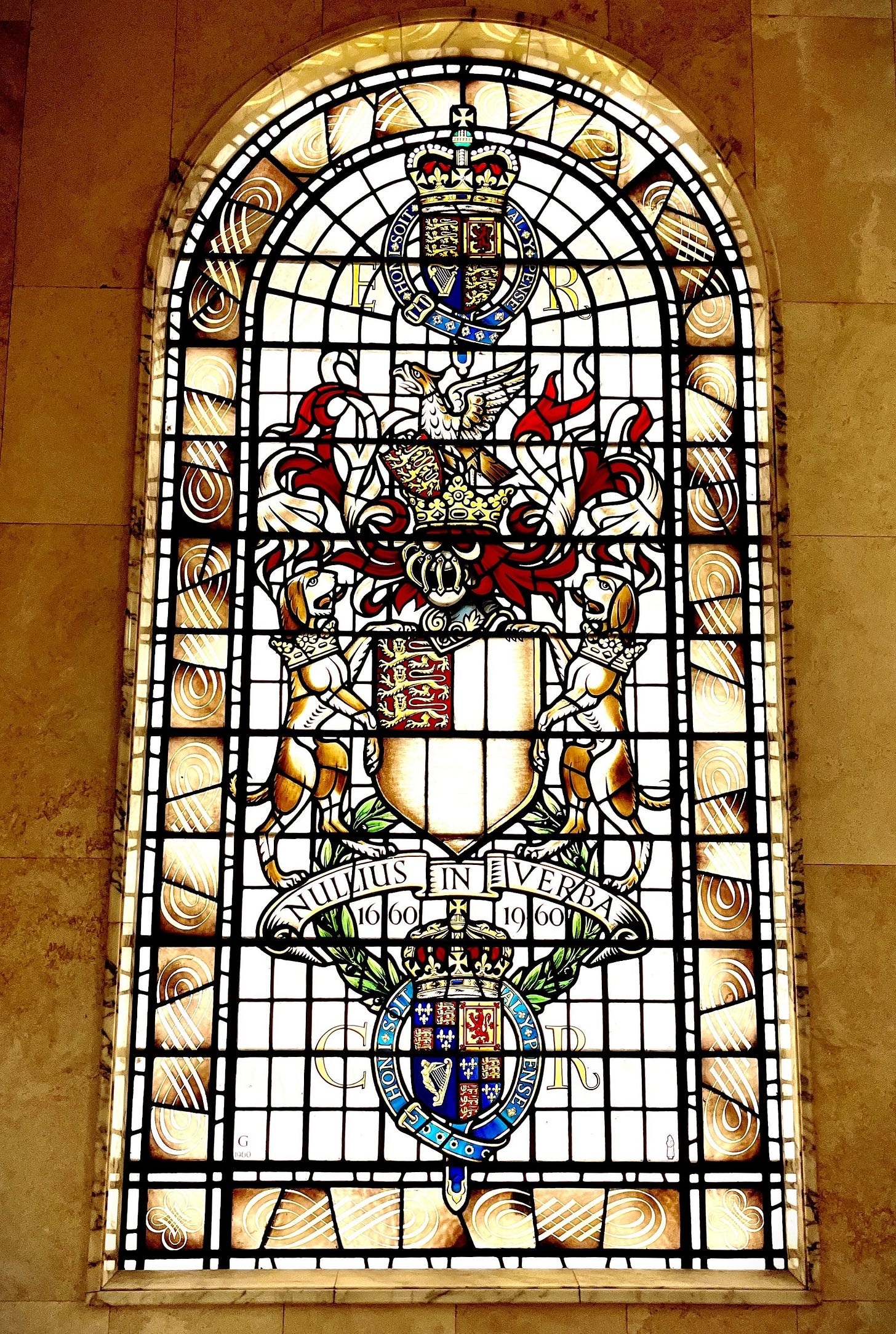

First, and most obviously, criticizing science is critical for science to progress. We would simply not have science without it. Being critical and reflective of our practices with an eye towards improvement is core to realizing any progress at all. The moment we collectively stop doing this is the moment we have failed to be serious scientists. I am personally taken by Merton’s norms of scientific practice, one of which is organized skepticism. Being skeptical and critical is fundamental to what we do.

My second reason for maintaining a critical demeanor in the face of attacks on science, however, appears to be less obvious to most people: I reject the premise of the question. There seems to be a belief that the criticisms made by scientists fuel the crusade against science. The implied counterfactual is that if science reformers were not so critical of scientific practice, then right-wing politicians and governmental officials would not have cause for attacking science. This is clearly absurd.

The core problem is the failure to recognize the crucial distinction between scientific arguments and ideological arguments. Everyone I know who is critical of scientific practice is doing so within the general terms of what we think of as science, relying on evidence and reason. These are not the same terms being used by those who are attacking science. They are playing an entirely different game altogether, one that is rooted in ideology. Scientific arguments are not going to be the criteria by which ideological crusades succeed or fail.

Of course, ideological arguments will ostensibly rely on scientific evidence, but this is all just smoke and mirrors, cover for conclusions that are fait accompli. The identical ideological arguments can be made based on entirely different sets of behaviors. If reformers weren’t loudly droning on about all of the problems of scientific practice, the idealogues could instead point to the lack of critical discussion within science, and a need for external authorities to provide what the community does not do for itself. If reformers weren’t loudly proclaiming that replication is the cornerstone of scientific progress, the idealogues could instead point to the lack of replications within science and therefore the uncertainty of scientific findings. Scientific arguments are entirely irrelevant to ideological goals, a key issue that many scientists don’t seem to understand.

I am reminded of the example my first mentor Dr. Tom Spencer would give when discussing qualitative differences in cognition across development: parents who are separating will sometimes sit down with their child and explain all the relevant facts and conditions that led to the separation, thinking that if they do so, then the child will understand the situation in the same way they do. This will not work, of course, because the children and adults do not make use of the same decision-making processes. Similarly, scientists seem to think if they just explain things better or differently—if people just understood the issues as they do—then of course everyone else will agree.

The relation between science and ideology is something I have engaged with before (here on this blog, and as a guest on Two Psychologists, Four Beers). My central arguments have been that a) it is really difficult to conduct research that is free from our personal ideologies, b) we tend to be pretty bad at recognizing how our ideological biases impact our research, and c) that we only treat perspectives that deviate from the normative ideology as ideological, whereas the normative ones are ideology-free. Importantly, these are descriptive claims, not normative claims, about the difficult relations between ideology and science. Those claims, however, are about scientific arguments and scientific arguments only. That is, scientific arguments can be intertwined with ideology, yet are nevertheless distinguishable from ideological arguments.

Criticizing science is critical for science to progress. We would simply not have science without it. None of this is to say that we should not be careful, considerate, and thoughtful about how we discuss our research, be it original substantive findings or criticisms of existing research. Indeed, “anticipation and harm minimization” is one of the themes of Responsible Conduct of Research. This responsibility, however, needs to be balanced with the imperative of organized skepticism and can’t be used as a mechanism to censor productive scientific work. It is also the case that some people are in precarious positions, in terms of employment or citizenship, and must be more cautious. That is why I highlight the importance of criticism as a collective enterprise. If we are collectively modifying our behavior according to how we think bad actors might use our work, then we have already lost the plot. Bad actors will selectively use scientists’ criticisms of science to further their goals, just as they will selectively use our research findings to further their goals.

So I will keep on being critical of science. I will do so because I believe in it, and I want us to all be doing the best work that we can. I hope that you will join me.

e.g., problems with social psychology, problems with personality psychology, problems with developmental psychology, problems with acronyms, problems with behavior genetics, problems with idiographics, problems with diversity in psychology, problems with people’s problems with open science, and so on.

It's a good post, thank you. I sometimes observe for myself that criticizing practices and writing op-eds about what work is needed is easier than doing that work. But, maybe that's specific to calling for particular kinds of evidence in a domain, rather than criticizing general problems. I certainly support loud, continuous skepticism and criticism.

Well said, Moin. I wrote a somewhat similar post this past weekend.